SICOT Global Network for Electronic Learning - SIGNEL

Case of the Month

Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar - Seremban, Malaysia

History

A 12-year-old girl referred to the Orthopaedic clinic with a 3-month history of intermittent limping on the left leg. She reports neither prior trauma nor medical illnesses. The limp was initially painless however, at presentation, she did describe occasional bouts of pain when she walked, particularly to her knee.

On examination, she had mild limitation of hip passive movement and palpation revealed a mass in her left inguinal region. Blood investigations revealed a raised CRP with a normal leucocyte count. Anti-Tuberculin test was significantly positive. Chest radiographs were clear. A pelvic radiograph was reported as normal. Due to the palpable mass in her left inguinal region, an MRI of the pelvis was performed.

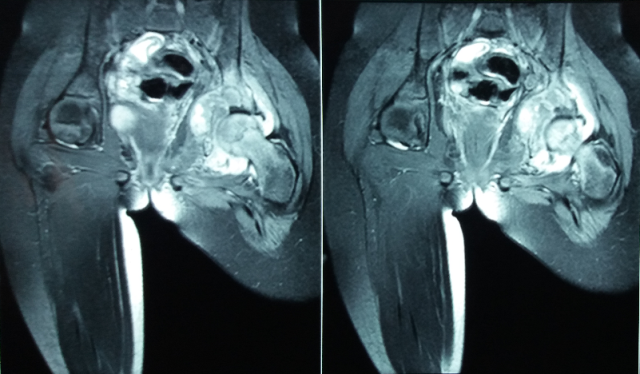

Figure 1: MRI of pelvis (coronal view)

Figure 2: Axial view MRI of pelvis

Q. What are you thoughts on the pelvic MRI?

MRI showed a mass within the medial side of the acetabulum involving both anterior and posterior columns (Figures 1 & 2). Axial views showed the medial acetabular mass (involving both columns; mainly posterior) and an enlarged lymph node.

Q. What is your next investigation?

CT scan of the left hip

Full body isotope bone scan

Biopsy of the mass

After discussion with the parents, an open excision biopsy was performed. To facilitate exposure of the medial acetabular wall and hip in this child, we employed a modified ilio-inguinal approach with an extension to incorporate an anterior, Smith-Peterson method to access the hip joint (Figure 3). A cortical window was made at the antero-medial dome of the acetabulum and a large volume of yellowish, semi-solid substance was curetted out. Following an anterior hip arthrotomy, no pus was observed and the joint was irrigated thoroughly. Multiple samples were sent for histology and microbiology cultures including those specific for tuberculosis (TB).

Figure 3: The post-operative scar showing our modified ilio-inguinal incision with an extension to incorporate a Smith-Peterson approach.

Following surgery, the patient recovered well. Histology showed chronic granulomatous tissue in keeping with TB. She was cleared of pulmonary TB and further investigations failed to reveal a primary source. She was started on the quadruple regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide which she will continue for the next 9 months. She was discharged 2 weeks after surgery and kept partial weight bearing for 4 weeks. At 2 months, she returned to school and is able to walk comfortably.

Discussion

In Malaysia, as in most endemic regions, there has been a rise in cases of tuberculosis (TB) over the past few years. Extra pulmonary TB constitutes about 10-11% of all TB presentations [1]. The clinical presentation, especially in the early stages, mimics several pathologies including Perthes disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, transient synovitis, septic arthritis, etc.. In regions where TB is endemic, it is wise to have a high index of suspicion and various authors routinely base their treatment on clinical and radiological findings alone [2].

Diagnosis of osseous TB can be challenging, particularly in the early stages. Blood investigations such as ESR and CRP are often elevated but are non-specific for TB. Mantoux/Anti-tuberculin tests are reported to have high false-positive results particularly after BCG vaccinations and can be misinterpreted in less experienced hands. Plain radiographs may show very little. MRI, though sensitive in detecting soft tissue abnormalities around the joint, is not specific to osseous TB. Definitive diagnosis therefore relies on culturing tubercular bacilli and/or histological diagnosis based on biopsy specimens. Routinely, biopsy and aspiration samples are sent for Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining, Acid-Fast Bacilli (AFB) smear and TB specific cultures. It is not uncommon to have high false negative results using staining methods and cultures may take a long time. PCR (polymerase-chain-reaction) testing, though highly sensitive and specific, are expensive and the cost considerations in TB endemic areas do negate its extensive use. Recently, novel methods are being proposed to aid the diagnosis of TB including the use of multi-targeted LAMP (Loop-mediated isothermal amplification) for osteoarticular tuberculosis with sensitivities and specificities above 90% [3]. Nucleic acid amplification tests including Xpert MTB/RIF also provide for rapid TB diagnosis (within hours) and further studies are required to ascertain their cost-effectiveness [4].

The mainstay of tuberculosis treatment is effective anti-TB chemotherapy (both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary). The World Health Organisation (WHO) has published tuberculosis treatment guidelines which are routinely updated (last revised in 2009). It recommends that newly diagnosed TB of bones and joints be treated for 9 months' duration with an early intensive phase consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol followed by a longer continuation phase consisting of isoniazid and rifampicin only. Alterations in these regimens are made in cases of multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB and previously treated patients (MDR can be as high as 80-90% in cases where initial TB treatment was unsuccessful). In such cases, drug-susceptibility testing is very important and should be used to guide treatment [5].

Specifically for paediatric tuberculosis involving the hip joint, the management depends on the stage of presentation (similar to adults). In the early stages of synovitis, apart from anti-TB medication, non-operative measures such as skin/skeletal traction is sufficient in preventing contractures and providing pain relief. The benefits of traction also include early assisted range of motion exercise of the hip. In very young children or if the child cannot cope with extended periods of traction, application of a hip spica may also reduce pain symptoms. With advanced joint disease, treatment is controversial especially in the setting of subluxation/dislocation. While some authors prefer avoiding surgery altogether, relying on the child’s potential of remodelling alone; osteotomies may be of benefit in ensuring proper acetabular-femoral head relations in the growing hip [6].

The prognosis is variable and better success is expected when TB is diagnosed and treated early. Long-term sequelae of hip tuberculosis included advanced arthritis and/or subluxations/dislocations. This in turn may result in the patient requiring excision arthroplasty or arthrodesis at bony maturity. Excision arthroplasty can be well tolerated with preservation of some movement and is inexpensive. However, the downside includes instability with weight-bearing and limb-shortening. Total hip replacement (THR) is gaining in popularity though there are concerns about TB reactivation. In a systematic review looking at articles published from 1950 to 2012, Kim et al showed that THR in the setting of active TB can have successful outcomes when performed in conjunction with thorough debridement and anti-TB medication [7].

In conclusion, TB remains a problem and the surgeon would be wise to maintain a high index of suspicion at all times. Even at this day and age, there remains issues with efficient diagnosis of extra-pulmonary TB and hopefully, this will improve with advancements in diagnostic technology. Anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment and surgery may aid in establishing the diagnosis. The real risk of reactivation will remain a problem for clinicians going forward as well as challenges with the growing numbers of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis cases.

- Swarna Nantha Y. A review of tuberculosis research in malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2014 Aug;69 Suppl A:88–102.

- Saraf SK, Tuli SM. Tuberculosis of hip: A current concept review. Indian J Orthop. Medknow Publications; 2015;49(1):1–9.

- Sharma K, Sharma M, Batra N, Sharma A, Dhillon MS. Diagnostic potential of multi-targeted LAMP (Loop-mediated isothermal amplification) for osteoarticular tuberculosis. J Orthop Res. 2016 May 13;

- Held M, Laubscher M, Mears S, Dix-Peek S, Workman L, Zar H, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Xpert MTB/RIF Assay for Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis in Children with Musculoskeletal Infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Jun 10;

- WHO | Guidelines for treatment of tuberculosis. WHO. World Health Organization; 2015;

- Moon M-S, Kim S-S, Lee S-R, Moon Y-W, Moon J-L, Moon S-I. Tuberculosis of hip in children: A retrospective analysis. Indian J Orthop. Medknow Publications; 2012 Mar;46(2):191–9.

- Kim S-J, Postigo R, Koo S, Kim JH. Total hip replacement for patients with active tuberculosis of the hip: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Bone Joint J. 2013 May;95-B(5):578–82.