SICOT e-Newsletter

Issue No. 57 - June 2013

History of Orthopaedics

A very brief history of orthopaedic surgery in United Kingdom

A very brief history of orthopaedic surgery in United KingdomAlistair Ross

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon - Bath, United Kingdom

It is impossible, in a short article, to acknowledge the contribution of the United Kingdom to world orthopaedics. All one can do is to focus attention on some of the major advances and recognise the surgeons, and others, who made them.

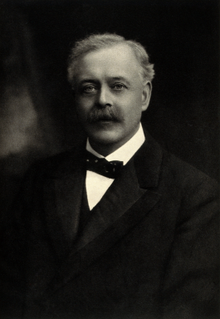

One starts with Hugh Owen Thomas (1834-1891), long considered the father of orthopaedic surgery in Britain. The son of a bone setter in Liverpool, he trained as a doctor in Edinburgh and at University College Hospital, London before returning to Liverpool where he treated fractures and tuberculosis, in particular. He is best remembered for the Thomas splint, notably used by his nephew, Sir Robert Jones (1857-1933), in the First World War to reduce the mortality of femoral fractures, and for Thomasâs test for fixed flexion of the hip. Jones himself studied with his uncle before eventually becoming Surgeon Superintendent of the Manchester Ship Canal. He established the first accident service in the world to treat the injured workers, experience which stood him in good stead when he organised the system of military hospitals and became Inspector of Military Orthopaedics (1916). By this time, he and Alfred Tubby had also organised a group of surgeons into the British Orthopaedic Society (1894) and subsequently, in 1918, he was one of a small group of surgeons who founded the British Orthopaedic Association. The Shropshire Orthopaedic Hospital, in Oswestry, was renamed the Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital in 1933.

Â

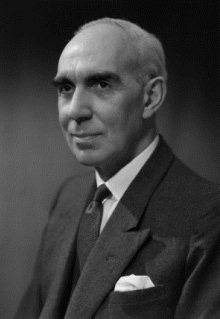

One of Robert Jonesâ protégés was Reginald (later Sir Reginald) Watson-Jones (1902-1972). After graduating from the University of Liverpool, he trained in London then returned to Liverpool as the honorary assistant surgeon in charge of the orthopaedic department and fracture clinic at the Royal Infirmary. Later, he too was appointed to the staff of the Shropshire Orthopaedic Hospital. He instituted an instructional course on fractures at the Liverpool Royal infirmary which became so popular that he was encouraged to write the first edition of his âFractures and Joint Injuriesâ. This was so successful that it ran to 15 editions under his authorship before being taken over, after his death, by JN (Ginger) Wilson under whose editorship it ran for a further seven editions. Watson-Jones adopted some of the European practices of internal fixation of the long bones but always believed these to be an âinternal sutureâ which he supplemented externally with plaster of Paris. He never wholeheartedly adopted the principles of the Swiss school. He was appointed civilian consultant in orthopaedic surgery to the Royal Air Force in the early 1940s and towards the end of the war became director of the Orthopaedic and Accident department at the London Hospital in Whitechapel. One of his greatest achievements was the establishment, in 1948, of the British volume of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery which ran successfully in association with the American volume until last year when the two volumes became separate. In his obituary, Jackson Burrows wrote that his writing âhad not only the essential virtues of clarity, simplicity, precision and brevity, but displayed also a splendid style of his own, always recognisable, exciting, stimulating and persuasiveâ, a style the Journal has tried to maintain. In addition to this he was, at various times, President of the British Orthopaedic Association, Vice President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and Orthopaedic Surgeon to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the latter the former Patron of the BOA.

The 1960s saw remarkable advances in the treatment of end-stage joint disease. At the forefront of these were John Charnley, later Prof Sir John (1911-1982), with his technician Harry Craven, but not to be forgotten for their place in the development of total hip replacement were Ken McKee of Norwich and Peter Ring of Redhill. Charnley worked on, and eventually perfected, the low friction arthroplasty with a stainless steel on high molecular weight polyethylene bearing, while McKee used a modification of the Thompson hemiarthroplasty combined initially with a metal cup designed by Watson Farrar and latterly a polyethylene cup designed by George Arden. Ring, meanwhile, distrusting polymethylmethacrylate cement, developed one of the earliest uncemented hip replacements based on the Austin Moore stem and a metal cup characterised by a long screw which fitted along the internal brim of the pelvis reaching almost to the sacroiliac joint. The Stanmore hip prosthesis was devised by John Scales, who was also responsible for the design of the massive endoprosthetic replacements which continue to be used in the treatment of bone sarcomas and other causes of major bone loss. It is probably fair to say that this early work laid the foundation for all subsequent joint replacement worldwide.

I have, during the course of this article, omitted the names of dozens of other great British orthopaedic surgeons who continue to enhance the contemporary international literature. Where would orthopaedic surgery have been without Bankart, Platt, Girdlestone, Trueta, Seddon and numerous others? Neither should we forget the contribution of Lister for his work on asepsis and Fleming, Florey and Chain for their identification and synthesis of penicillin, without whose discoveries much of modern orthopaedics would be substantially more hazardous, nor, indeed, those of Hounsfield (CT) and Mansfield (MRI), both winners of the Nobel Prize for their contribution to modern methods of axial imaging.

British orthopaedics has, at various stages in its evolution, led the world in the development of new ideas and new techniques. As in other disciplines, these have been adapted and improved upon, often to the financial advantage of others, but those who were brave enough to have faith in their original concepts should not be forgotten, particularly by those who have adopted their ideas with minor revision and added their name to them.

Â

Robert Jones |

Reginald Watson-Jones |

The 1960s saw remarkable advances in the treatment of end-stage joint disease. At the forefront of these were John Charnley, later Prof Sir John (1911-1982), with his technician Harry Craven, but not to be forgotten for their place in the development of total hip replacement were Ken McKee of Norwich and Peter Ring of Redhill. Charnley worked on, and eventually perfected, the low friction arthroplasty with a stainless steel on high molecular weight polyethylene bearing, while McKee used a modification of the Thompson hemiarthroplasty combined initially with a metal cup designed by Watson Farrar and latterly a polyethylene cup designed by George Arden. Ring, meanwhile, distrusting polymethylmethacrylate cement, developed one of the earliest uncemented hip replacements based on the Austin Moore stem and a metal cup characterised by a long screw which fitted along the internal brim of the pelvis reaching almost to the sacroiliac joint. The Stanmore hip prosthesis was devised by John Scales, who was also responsible for the design of the massive endoprosthetic replacements which continue to be used in the treatment of bone sarcomas and other causes of major bone loss. It is probably fair to say that this early work laid the foundation for all subsequent joint replacement worldwide.

I have, during the course of this article, omitted the names of dozens of other great British orthopaedic surgeons who continue to enhance the contemporary international literature. Where would orthopaedic surgery have been without Bankart, Platt, Girdlestone, Trueta, Seddon and numerous others? Neither should we forget the contribution of Lister for his work on asepsis and Fleming, Florey and Chain for their identification and synthesis of penicillin, without whose discoveries much of modern orthopaedics would be substantially more hazardous, nor, indeed, those of Hounsfield (CT) and Mansfield (MRI), both winners of the Nobel Prize for their contribution to modern methods of axial imaging.

British orthopaedics has, at various stages in its evolution, led the world in the development of new ideas and new techniques. As in other disciplines, these have been adapted and improved upon, often to the financial advantage of others, but those who were brave enough to have faith in their original concepts should not be forgotten, particularly by those who have adopted their ideas with minor revision and added their name to them.

Â