SICOT e-Newsletter

Issue No. 55 - April 2013

Editorial

Should scoliosis screening for school children be introduced or continued?

Should scoliosis screening for school children be introduced or continued?

Keith DK Luk

President-Elect SICOT - Hong Kong

There are many causes of scoliosis including congenital malformation, neuromuscular diseases or as part of a syndromal disorder. However, the etiology of 80% of scoliosis is still not yet known. They appear and progress at the growth spurt during the early teens and are thus called adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). The reported prevalence of curves of Cobb angles >10° ranged from 0.1-7% but only 0.1-1.4% exceed 20°. If left untreated a small percentage of them may progress leading to severe clinical deformities, cardiopulmonary compromise, earlier onset of low back pain, and not the least, psychosocial burden on both the adolescents and the parents. Non-invasive bracing could be used to arrest progression when the curve is mild and detected early. For large curves or rapidly progressive curves in the skeletally immature, surgical correction and fusion of the spine may be necessary. Earlier detection and diagnosis of AIS would therefore hopefully minimize the risk and costs associated with surgery.

Screening for spinal deformity amongst the adolescents was first started in the late 1950s in Delaware, USA, followed by implementation in Canada, some European and Asian countries using different screening protocols. Participation was voluntary in the majority, except for Japan and some states in the USA. In 1996, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended âneither support nor oppositionâ to scoliosis screening because of lack of sufficient evidence either way. Interestingly, they changed their recommendation to âagainst screeningâ in 2004 without newer information, but mainly because there was a lack of evidence of an effective conservative treatment method even if the scoliosis were detected early. This recommendation has been heavily challenged and the value of scoliosis screening has remained controversial since. On a positive side, it has prompted a number of high quality studies and systematic reviews in the past decade including a series of published works from our centre in Hong Kong in the last few years.

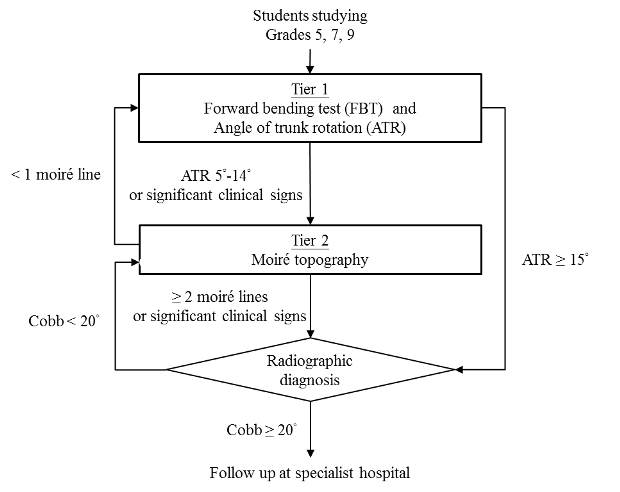

An ideal population scoliosis screening program should be highly sensitive (at least 70%), specific and predictive (a positive predictive value - PPV of between 30-50%), with minimal referral rate, safe and inexpensive. The specificity and negative predictive values (NPV) are less of a concern because they are often high due to the lower prevalence of AIS. Although radiography is very sensitive in confirming the diagnosis it is obviously not the screening tool of choice because of the radiation risk and the cost. The forward bending test (FBT) is the most commonly used method. It is cheap, safe, rapid, and can be easily performed on a large population. However, it is operator dependent leading to many false positive and false negative cases. The angle of trunk rotation (ATR) at the rib hump measured with a scoliometer has been found to correlate well with Cobb angle on the radiograph. A cutoff value of 5° ATR is commonly used for diagnosing scoliosis. The Moire topography was developed and popularized in Europe. It makes use of a biosterometric technique by casting the shadow of a set of grid lines over the back of the upright subject. The contour lines on the back resemble the altitude lines on a map that delineates the height of the mountain and the depth of the valley, thus revealing the amount of asymmetry between the two sides of the back. This technique incurs a small investment on the grid but otherwise the recurrent cost is negligible. It is very safe because it is only an optical method. From the literature it is evident that any of the above methods when used alone would produce low sensitivity and specificity. However, when used in combination the results are very satisfactory.

I was responsible for initiating the scoliosis screening program in Hong Kong in 1995, taking advantage of the commencement of an annual physical check-up program offered by the Student Health Services then. A tier system was designed in which the family physicians involved were trained to perform the FBT and ATR measurement in tier 1. If the ATR is >5° the student will undergo the Moire topography at a tier 2 special clinic. Failing the cutoff criteria of >2 Moire line difference between the two sides of the back, an X-ray will be taken. The patient will only be referred to the tier 3 scoliosis clinic managed by a trained scoliosis surgeon if the curve has a Cobb angle of >20° (see appendix below). The program is offered to all school children starting from grade 5 (around 10 years old) and they will be screened annually until skeletal maturity. To date, more than 1.2 million episodes of examination have been performed and 115,190 of the students screened have already reached maturity. This is an important issue because we all know that if a girl is screened negative for scoliosis at the age of 10 it does not necessarily mean that she will not develop a scoliosis in the later years. There is only one other program in the literature that had followed their subjects to maturity but unfortunately their cohort size was very small with only 2,242 subjects.

In a meta-analysis conducted by our group where 36 cohort studies from different countries between 1977 and 2005 were included, the pooled referral rate for radiography was 5%, within which only 5.6% had Cobb angles of >20°. These very low PPVs indicate that many students were unnecessarily referred. This can be easily explained by the heterogeneity in the screening tests, the referral criteria used and the diversity of follow-up rates. For example, when the FBT was used alone many more children would have been referred for radiographic assessment. On the contrary, our referral rate in Hong Kong for radiography was 2.8% with a very reliable 95% confidence interval of 2.7-2.9%. The sensitivity and PPV for detecting a >20° curve was 88.1% and 43.6% respectively. The corresponding specificity and NPV were over 95%.

The cost of a screening program is an obvious concern to the health care provider. Some studies included only the cost of the screening while others have included that of the diagnostics and subsequent brace treatment or even surgery. It is therefore hard to compare between countries where different health care systems are in place with different funding mechanisms. Suffice it to say the cost of screening one student in our Hong Kong cohort reported in 2012 was US$55, which is very similar to US$54 in a study from Rochester, Minnesota, USA, reported in 2000 after adjusting for inflation.

From our experience over the past 18 years we have found a tiered screening program using a combination of tools is not only effective in identifying AIS patients who require follow-up management but is also inexpensive and sustainable. What we have not been able to show is whether the rate of surgery has been successfully reduced as a result of the earlier diagnosis. Whether brace treatment is truly effective in changing the natural history of the curve progression is another subject that deserves further research. One thing for sure is that our community is now much better educated about this condition. When I was an orthopaedic resident in the late 1970s, most of the surgeries were performed on late presenters with curves of >70-100°, both because of ignorance of the parents and, regrettably, also some frontline doctors. Today, the majority of surgical cases are those who have failed conservative bracing with curve magnitudes in the low or mid 50s°. Neglected cases that upon first presentation deemed requiring major vertebral resections are now rare. The reverse trend is being observed recently in Norway where unfortunately they have given up their screening program since 20 years ago. Earlier and easier surgery may not be good news for the technical surgeon but is certainly the best news for the patients and their families.

We understand our SICOT community covers countries with very different systems with different health care priorities and financial constraints. However, in my mind scoliosis screening is very worth introducing or continuing, if resources permit. Prevention is better than cure, but if it is not preventable then an earlier diagnosis and timely intervention is the next best we can do.

Â

Further reading:

-

Fong, D. Y., Lee, C. F., Cheung, K. M., Cheng, J. C., Ng, B. K., Lam, T. P., . . . Luk, K. D. (2010). A meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of school scoliosis screening. Spine, 35(10), 1061-1071. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bcc835

-

Lee, C. F., Fong, D. Y., Cheung, K. M., Cheng, J. C., Ng, B. K., Lam, T. P., . . . Luk, K. D. (2010a). Costs of school scoliosis screening: A large, population-based study. Spine, 35(26), 2266-2272. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cbcc10

-

Lee, C. F., Fong, D. Y., Cheung, K. M., Cheng, J. C., Ng, B. K., Lam, T. P., . . . Luk, K. D. (2010b). Referral criteria for school scoliosis screening: Assessment and recommendations based on a large longitudinally followed cohort. Spine, 35(25), E1492-1498. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ecf3fe

-

Lee, C. F., Fong, D. Y., Cheung, K. M., Cheng, J. C., Ng, B. K., Lam, T. P., . . . Luk, K. D. (2012). A new risk classification rule for curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Journal.

-

Luk, K. D., Lee, C. F., Cheung, K. M., Cheng, J. C., Ng, B. K., Lam, T. P., . . . Fong, D. Y. (2010). Clinical effectiveness of school screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A large population-based retrospective cohort study. Spine, 35(17), 1607-1614. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c7cb8c

Â

Appendix